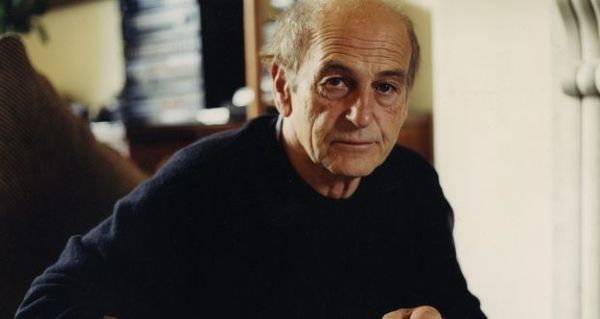

Tom Murphy, the acclaimed Irish playwright, died this month at the age of 83. This tribute by Faculty Fellow Declan Kiberd was published originally in The Times of London, 20 May 2018.

Tom Murphy: A Broker in Risk, by Declan Kiberd, Donald and Marilyn Keough Professor of Irish Studies, Professor of English and Irish Language and Literature, The University of Notre Dame.

Theatre tends to be conservative. Forms, once successful, are often repeated; and people pay good money to see what they enjoyed before. Many effective but repetitive playwrights achieve at about the age of thirty a technical competence which leaves them immune to criticism---and incapable of development. In that process, vibrant form can become dead formula.

Tom Murphy did not play by those rules. He was, instead, a broker in risk, far more than any of the spec builders or flashy businessmen whom he satirized in plays. He never repeated himself but kept trying strange forms and new themes. He didn’t just report known emotions: he invented new kinds of feeling onstage in works like The Morning After Optimism. He spoke for and to people whose lives seemed like a preparation for something that never actually happened.

In the work, imaginative audacity was, almost invariably, made incarnate in immaculate form. Each play sought to raise theatre to entirely unprecedented levels of emotional intensity, while flirting at the same time with the dire possibility of total failure. Yet even Murphy’s flops were somehow more exciting than most other people’s successes. He just didn’t care---as long as he had tried for perfection. And he achieved the sublime in The Gigli Concert.

It is a play which, likes its characters, aspires to the condition of music. If the dramas of Shaw and Synge (with their arias, duets and allegro effects) had sometimes verged on opera, Murphy in that work really did break through to pure sound; and he found the perfect director in Patrick Mason.

“Tom Murphy hears sound as character”, said Mason (who was once a voice coach), “and he expresses character as sound”. In the play the Irish builder who wishes to sing like Beniamino Gigli says “I could always size a man up more from the sound than from what he’s saying”. It was Murphy who made the break-through to the kind of “verbal opera” towards which even the most gifted previous playwrights had merely gestured.

When Tom Hickey, in one of the great acting performances of modern theatre, seemed to sing like Gigli by sheer power of will and imagination, he showed the Irish builder how a mere human could achieve heavenly harmonies. In that moment Murphy had (like the greatest artists) tamed the demonic; and the energy of life had found its justification as pure form.

The religious language is not exaggerated: art could raise people to godlike powers. Most of Murphy’s major plays move well beyond the given world of dull realists to a place of redemption. Yet many of his protagonists are also deeply frightened by that very supernatural zone which their own yearnings have made possible. Murphy was, more than once, honest enough to confess to that fear in himself.

Yet, for him, the artist had assumed the role of the priest in the attempt to replace a fallen human nature with a more angelic world. The theatre was in his view the new sacred space; and all of the old holy places must be broken into and reclaimed (as in The Sanctuary Lamp) by those who seemed the least saintly sorts. He was at one with the Beats in his conviction that the truly holy ones were the wild, untamed, deranged visionaries.

Murphy’s world was always one in which it was “too late for logic”. From the outset of his career in the 1950s, he was critical of timid rationalists and of their preferred mode: realism in art. “One thing is sure” he said of his first play written with Noel O’Donoghue: ‘it is not going to be set in a kitchen”. That mordant comment was made at a time when so many pans of rashers and sausages were fried on the stage of the Abbey that some wits claimed its actors were the best-fed theatre company in the world.

Yet he did eventually enjoy many nights of triumph in the Abbey himself. His early work explored the inarticulacy of wounded males in a culture more often known for the gift of the gab. His later plays, after Bailegangaire, extended this investigation to the hurt Irish female.

Rejecting merely realist modes, Murphy worked best by trial-and-error, conducting intense workshops with actors as they shaped raw scripts designed to probe the unknown and unsafe. There were other great playwrights at work in English during his long, astonishing career as a writer: but none who could match his remarkable combination of hilarious dialogue, baffled silences and emotional intensity.

He learned from the best----but he was a once-off. His art has inspired some of the finest playwrights of a succeeding generation. Marina Carr, Frank McGuinness and Conor McPherson have risen gloriously to his challenges—as in the United States did the script-writers of The Sopranos. Ireland has long known his greatness: and the wider world is coming, a little more slowly, to recognize it too.

Declan Kiberd’s latest book is After Ireland: Writing the Nation from Beckett to the Present (Harvard University Press, 2018).

Photo credit: Paul McCarthy, The Irish Times, 5 October 2017.