Haunted Ireland: Ghosts, Specters, & Spirits in Irish Literature

#Wanderlust: Medieval Pilgrims, Instagram, Influencers, and Self-Love

The Great Forgetting: The Work of Women's Writing

The Metropolis and Modern Life

Ethics and Affects in Medieval Heroic Literature

The Historical Novel

Voracious Reading: Literature and/as Consumerism

Crazy Diamonds: The Madwoman in Literature

Reading the Refugee

Each course in this intriguing array was designed and taught by an English PhD student earning an Irish Studies graduate minor.

All are the fruit of a professional development plan—both intentional and intensive—that the Department of English has created for its graduate students.

Teaching as “A Way of Thinking”

“Our English faculty choose to characterize teaching as a way of thinking,” says Kate Marshall, Associate Professor of English and Director of Graduate Studies. “The goal is to integrate teaching into overall scholarly practice.”

The starting point for English doctoral students as they share in this endeavor is the practicum “Teaching Writing,” which prepares them for teaching two semesters of the University’s first-year undergraduate “Writing and Rhetoric” course. Depending on their individual research interests, graduate students may also spend one or more semesters at this stage as teaching assistants in courses as varied as “Great Irish Writers,” “Introduction to Gender Studies,” or “Medieval Literatures.”

“The most exciting opportunity comes next,” Professor Marshall explains. “It is designing and pitching a lower-division English course first to the Department and then, if successful, to the University Curriculum Committee. While a competitive process, it is one in which students are mentored intensively along the way. Through workshops and in one-on-one sessions, faculty and more senior graduate students coach students in how to think about creating and shaping a course that situates their own academic interests within the University’s core requirements.”

And, of course, the title and subject matter must appeal to Notre Dame undergraduates.

Some key tips she and other mentors share with students for both winning the required approvals and having undergraduates thrive in the class:

- Think like a non-major;

- While the course you design will most likely have the subject of your dissertation at its core, broaden it thematically and by timeline;

- Choose a subject of intense interest to you, because doing so will make for a more interesting class and make you a better teacher.

“Understanding how a newly designed course fits into both lower-level course paradigms and an institution’s undergraduate culture,” Professor Marshall points out, “builds skills that will be applied throughout one’s professional life.”

Once through the administrative process, there comes the moment of actually teaching the course. It is here, in the classroom, that making questions and themes come alive becomes a transformative experience not only for the undergraduates but also for the graduate-student teachers. As teachers, they will both encounter new perspectives on familiar texts and discover how new texts might illuminate or amplify familiar themes. It marks the beginning of their own practice in making teaching “a way of thinking.”

Designing a course as a way to construct “an alternative route of enquiry”

Julian Dean is a fourth-year graduate student whose broad interests are Irish literature, modernism, postcolonial literatures and theory, critical theory, and the Anthropocene. His dissertation examines how, in various postcolonial settings, authors like W. B. Yeats, Wole Soyinka, and Athol Fugard used tragedy to conceive alternatives to the nation state.

Having won approval from both the department and the University Curriculum Committee, Julian is teaching “Haunted Ireland: “Ghosts, Specters, & Spirits in Irish Literature” this spring term.

“With my training firmly rooted in Irish Studies,” he says, “I started my thesis by writing about Yeats. As that chapter came into fruition, I was left with dozens of ideas about texts that did not fit into the limited space of my dissertation. I was fascinated by the spiritual and the occult, and knew that these topics were ones I would like to explore further. My syllabus for the ‘Haunted Ireland’ course became a tentative ‘works cited’ and thesis all rolled into one. In this way, my course is both an alternative route of enquiry and a break from the singular track of my dissertation.”

The 20 undergraduates enrolled in “Haunted Ireland” have begun the term with poems in the 18th-century Bardic tradition. They will go on to read and discuss Bram Stoker’s Dracula, W.B. Yeats’s Words Upon the Window-Pane and Purgatory, James Joyce’s The Dead, Marina Carr’s The Bog of Cats, and Anna Burns’s Milkman.

As Julian and his students read these texts together, they will explore how authors use the ghostly to grapple with very material problems of the time—from the Acts of Union to the Land War and all the way through to “The Troubles” of the late 20th century.

Teaching undergraduates to approach texts with “passion and insight”

Fellow fourth-year doctoral student Anila Shree has interests that include 18th century British and Irish literature, women’s writing, cultural studies, the novel, and theories of fiction. Her dissertation rethinks women’s writing of the early 18th century by establishing a counter-tradition of prose fiction that goes beyond the English novel.

After successfully constructing and pitching her course “The Great Forgetting: The Work of Women's Writing,” Anila entered the classroom in the Fall 2020 semester with a syllabus that included texts by Margaret Cavendish, Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, Virginia Woolf, and Audre Lorde, as well as films, podcasts, and songs.

The global pandemic made Anila’s classroom an entirely new one, encompassing both the real and virtual space. The real classroom required masks, distancing, and a plexiglass barrier. Simultaneously, she orchestrated a virtual classroom for students isolating or quarantining.

“An important aspect of the class,” she explains, “was to approach the work of reading women’s writing as an explicitly political act of remembering, understanding, and reshaping the canon. In teaching it, I realized emphatically that once each student understood and shared these objectives as a group, we could develop an atmosphere of curiosity and discovery.

“The added challenges of the global pandemic shaped our entire learning experience,” she acknowledges, “but our commitment to teamwork, to shared decision making, and to the objectives of the class helped us to ride through some of those unavoidable obstacles. Whether we met online or in-person, we strove to discuss our texts with passion and insight.”

__________________

Discussing texts “with passion and insight” is an endeavor that Julian, Anila, and their fellow graduate students bring daily to the University community.

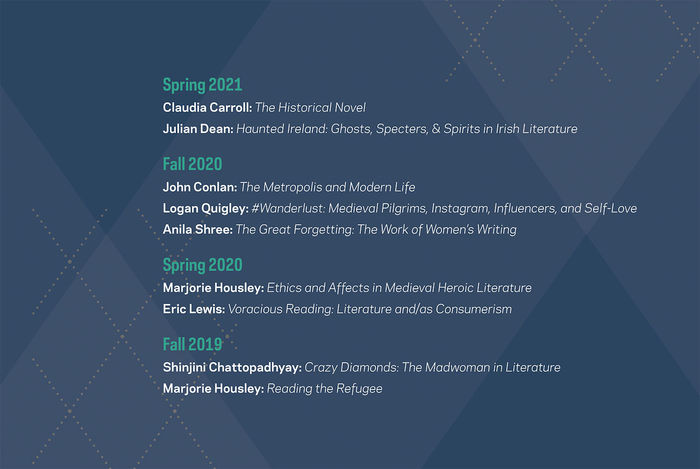

A compilation of English PhD students earning an Irish Studies minor and the undergraduate courses they have taught over the past two years is impressive in its diversity of themes and approaches: