Absolution Under Fire

Paul Henry Woods

Absolution Under Fire, 1891

Snite Museum, The University of Notre Dame

Paul Henry Woods (1872-1892)

LITERARY REFLECTION

David Carlson

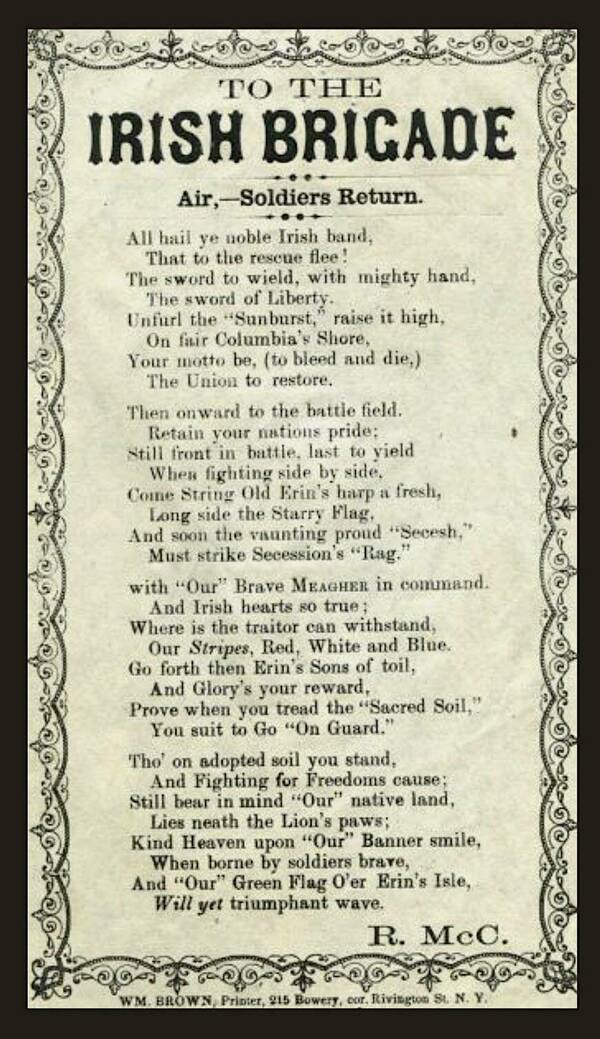

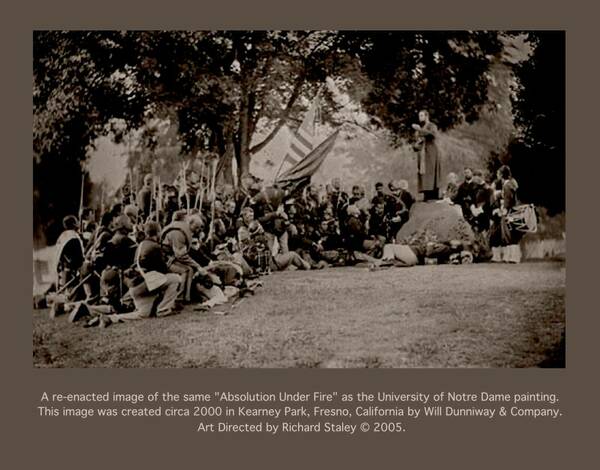

Paul Henry Wood's Absolution Under Fire depicts Notre Dame professor-turned-U.S. Army Chaplain Reverend William J. Corby, C.S.C., providing a general absolution to men of the Irish Brigade during the Battle of Gettysburg in the U.S. Civil War. Its history covered well by others, the painting offers a quintessential blend of God, Country, and Notre Dame. Produced by a Notre Dame student at a time when Irish immigrants and American Catholics were working to prove their compatibility with American democracy, the work touches on themes like patriotism, Irish immigration, Catholicism in America, Notre Dame’s long relationship with the U.S. military, Civil War memory, and the experience of war itself.

War belongs to that family of human experience the essence of which, those who have endured it assure us, defies communication. One simply cannot understand war without experiencing it firsthand. But this truism does not stop and even fuels the perpetual stream of art, print, and film trying to grasp at its gnostic reality. It is not enough to ensure one’s audience that War is Hell, because for some this adds to the allure. Emphases on the blood and guts and the collateral damage as deterrent fail to account for the fact that some people seem rather to enjoy it. Besides, if it cannot be expressed, that allows just that critical sliver of doubt in those minds hellbent on pursuing it to assure themselves and others that it can’t be as bad as all that.

Issues compound when the subject matter is something as emotionally and politically charged as the U.S. Civil War. The passage of well over a century has yet to render uncontroversial the essential nature of that conflict. Questions of personal, communal, and national identity remain so intimately linked to its memory and commemoration that perhaps the invitation to commemorate it in florid and dramatic terms bordering on the sacral is irresistible. This dramatization sacrifices something of the uncertainty experienced in the moment. It may be quite noble to die—perhaps less to kill—in the service of a great cause, but even a war as ostensibly high minded as the one that came to the United States in 1861 provoked consternation. In his second Inaugural Address Lincoln said to the nation and its future descendants that upon his first election “all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it - all sought to avert it.” We might forgive Lincoln some rhetorical flourish. Wars don’t start themselves. Someone always shoots first, as we all had occasion to remember in 2022. Sometimes one finds that the war has come regardless of personal preference or ideology. Perhaps you, too, saw the footage of men trying to flee their stricken country stopped at checkpoints and being torn from their screaming wives and mothers for service at the front lines. In such moments perhaps the notion of noble sacrifice and glorious bloodshed provides a measure of encouragement to those who find themselves having a gun put in their hands whether they want it or not.

For my part, and I of course speculate as others lacking the direct experience, I have long suspected that portrayals of war—even the ones that others as clueless as myself assure me ring true—generally fail to account for its dull banality. Recently I happened to see a video posted by a friend of mine with no hint to its content other than a title added by this friend: “The Male Experience.” I came to learn that in this video, which I suppose must have been filmed in Ukraine, a man steps out of an armored vehicle and almost immediately onto a land mine. He survives the initial blast and somehow maintains the presence of mind to wrap a tourniquet around his leg, which is now reduced to a few ribbons beneath the knee. Once tied, he begins a painful yet prompt crawl back to the vehicle, where a comrade helps pull him inside. As he vanishes into the hull, we see a still-attached booted foot trail along behind him. The hatch closes with a generous streak of red tracing the path of the wounded man. I cannot of course say how if at all this moment’s commemoration will come in the future; the vehicle, like the war, simply drove on.