“Chin Angles” or How the Poets Passed (early to mid 1920s)

Isa (Isabella) Macnie

“Chin Angles” or How the Poets Passed (early to mid 1920s)

pen, ink and watercolour on paper

<Original, one of two versions>

Isa (Isabella) Macnie (1869- 1958) (Irish artist, cartoonist)

PROVENANCE: The Ernie O’Malley Collection; The O’Brien Collection

LITERATURE: Published initially in the New York Times, then the Irish Independent (26 Sep 1924) and then in the American Forum; Oliver St. John Gogarty’s memoir, As I walked Down Sackville Street (1937)

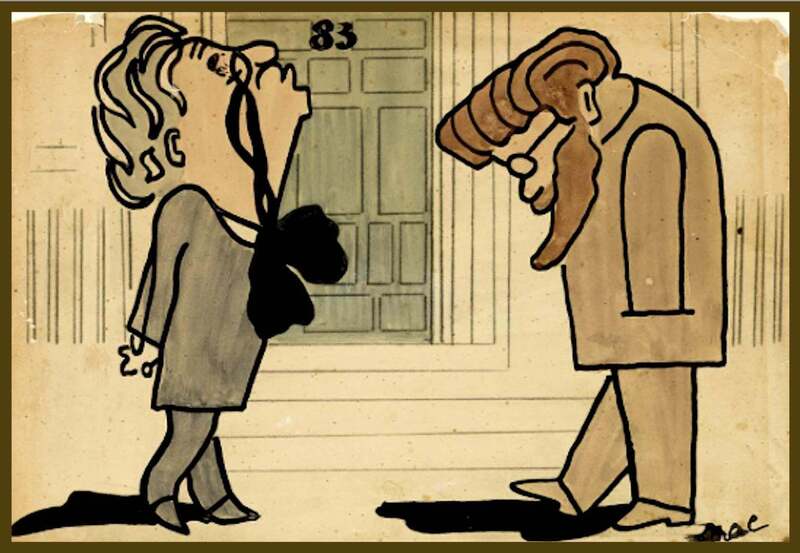

The cartoon depicts W.B. Yeats and George Russell ("AE") walking past 83 Merrion Square to visit one another without seeing each other. (It apparently depicts a real event!)

It has been reproduced extensively; was referred to in Sean Piondar’s March 1945 Questionnaires to Celebrities No. 24 “Mac”, published in some magazines, such as the Dublin Magazine, pp. 3-4 as well as Frank Bouchier Hayes’ article on ‘The rich and varied life of a forgotten Dublin Cartoonist’ on 5 March, 2010 in Pue’s Occurrences.

The caricaturist Isabella Mary Macnie, known as MAC, was born in Clontarf, Dublin in August 1869. Her father was a Scottish master printer and Justice of the peace. Macnie was a renowned “polymath”: a skilled sports woman and in 1907 became the Irish Ladies' Croquet Champion; an actress; sketch writer; composer; pianist; artist/cartoonist as well.

Macnie took up cartooning in her fifties. She used the pen-name Mac in the publication of her cartoons which tended to cover political figures of the day. Macnie was also an active suffragist and philanthropist.

She was a member of the Dublin University Dramatic Society, the Dublin United Arts Club and the Irish Women's Reform League. She did charity work to support the victims of the Titanic disaster and, during the First World War, nursing and the Red Cross.

She published her book of caricatures, 'The Celebrity Zoo' with accompanying desultory rhymes and 20 caricatures in 1925.

“Chin Angles:” Frenemies in the Free State

Julian Breandán Dean, PhD

Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies

University of Notre Dame

Isa “Mac” Macnie’s caricature of William Butler Yeats and George Russell [who used the pseudonym "AE"], “Chin Angles,” is a brilliant snapshot of a time, a place, and a very complex and often antagonistic friendship. The time is in the immediate aftermath of the foundation of the Irish Free State. The place, more specifically, is Merrion Square, Dublin. Indeed, we can see between the two figures the exact address of 83 Merrion Square. And this is the joke. Yeats, at this time, lived at 82 Merrion Square while Russell worked at 84 Merrion Square. The two friends (though this at times may be too strong a word) are depicted here walking to meet each other—though they will pass each other as Yeats has his nose in the clouds and Russell his eyes to the ground. In the 1920s, Merrion Square was a very fashionable neighborhood due to its famed Georgian architecture and its proximity to Leinster House and the newly formed Oireachtas. It is likely the setting evoked in Yeats’s poem “Easter, 1916”:

I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Though, Macnie portrays a slightly different Yeats here. He is no longer a poet of or among the people who might pass a polite, meaningless word or two in the street. Instead, as she makes clear in her book The “Celebrity Zoo” (First Visit): Some Desultory Rhymes and Caricatures, Yeats is now the proud owner of Ireland’s first Nobel Prize. Depicted as a camel, Yeats has his nose in the air just as he does in “Chin Angles” and Macnie both mocks and reinforces the idea of Yeats’s celebrity in “The Camel”:

As you survey this Camel, with surprise,

You’ll recognize it as a Nobel Prize,

When it walks calmly, with uplifted nose,

I’m sure it’s nearer Heaven than to its toes.

Russell is also treated in Celebrity Zoo with allusion to his facial hair.

Though you might think this beast was mostly hair,

A Poet lies concealed behind its fur.

(If, like most others, you revere this bear,

At calling it a “beast” you will demur.)

More!...for its fur, in manner cabalistic,

Contains in one a Poet, Seer, and Mystic.

Clearly, Macnie’s treatment of Russell is a bit gentler. The joke is at the expense of his chosen aesthetic and not his perceived arrogance. Furthermore, she makes a point of noting that most people seemed to “revere” George Russell. Russell’s work at the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society and his generosity are both captured in Joyce’s Ulysses. Despite some gentle mockery here too, Joyce points out via his autobiographical character Stephen Dedalus that it was thanks to Russell that he was first published. Hence the famous pun, “AEIOU” (of course, Russell also sent the young Joyce to both Lady Gregory and Yeats for assistance and both did their utmost to help Joyce. During his first trip to Paris, Joyce stopped over in London to meet Yeats who fed him and set him up with contacts for work. But, WBYIOU must have stuck in Joyce’s throat). In his Autobiographies, Yeats describes Russell as “in the eyes of the community, saint and genius” (195). While at times this community included Yeats, it did not always. The two had more than a few disagreements over their five decades of interactions. Yeats would in fact describe their relationship as “the antagonism that unites dear friends” (and that is the subtitle of Peter Kuch’s excellent book on the two poets).

They were, perhaps, too similar. They mirrored each other in ways that would prove at times reassuring and at others irksome. For instance, they both rejected traditional Christianity in favor of something a bit more esoteric. In the 1890s, both were members of the Dublin Theosophical Society, and the visionary and mystical would bind the two men for the rest of their lives. But while AE, to use his occult name, would think of himself as a mystic and would speak of visions, Yeats, or Demon est Deus Inversus (DEDI for short) to use his occult name, would think of himself as a mage and practitioner of occult magic. While both were outside the norms of scientific materialism and Catholic conservatism, they were dialectically opposed in many ways. AE sought to bring visions from an ideal plane to this one. DEDI sought to control this plane via magic pulled from the ideal plane. This desire to control was at the heart of their most profound and lasting disagreement.

Russell was, outside of his work as an agricultural economist, primarily known as a poet and painter. But, he did venture into playwriting in direct response to a play by Yeats and George Moore. Yeats and Moore collaboratively (another too strong word) wrote Diarmuid and Grania for what would be the final season of the Irish Literary Theatre in 1901. Russell, like much of Dublin, was offended by the overt sexuality and modern language used in the retelling of part of the mythic cycle. Russell decided to reprimand Yeats and Moore by writing Deirdre, another tale from the mythic cycle that also deals with a beautiful young woman attempting to avoid marriage to an older man. Dierdre would be performed by Willie and Frank Fay’s theatre company and Maud Gonne’s Inghinidhe na hÉireann in a split bill with Yeats and Gregory’s Cathleen ni Houlihan. While the former has been mostly forgotten and the latter remembered as a seminal work in Irish theatre, Russell’s play would introduce him to the theatre and to Yeats’s complex machinations towards absolute control of a theatre company. Machinations that would lead to a near irreparable split.

Yeats was asked by the Irish National Theatre Society—the group formed in the wake of the productions of Deirdre and Cathleen ni Houlihan—to be president. But he was only asked after Russell turned it down. Nevertheless, the two men would deal with a host of controversy in the early years of the Irish theatre. One early controversy over the choice of plays led Russell to create a set of rules that gave votes for play choices to all members. This democratic approach was not Yeats’s vision of the theatre. Yeats wanted to be free to produce plays for his aesthetic aristocracy—those few individuals who could appreciate what he deemed high art. Indeed, after the first performance at the Abbey Theatre, Yeats would enumerate the importance of who each play should please to a rather shocked audience: “Does it please us?” and only after that, “does it please you?”

Russell, serving as vice president of the Society, effectively resigned in 1904 over a dispute with Yeats over intellectual property. Russell had given permission to a group of actors either formerly or loosely associated with the Theatre Society to take Deirdre to America. Yeats was furious. He had only just returned from a speaking tour of America and had grand money-making schemes for bringing the Theatre Society to do a tour of the US. As an amateur group, this was unrealistic, but he viewed Russell’s permission as a betrayal. Nevertheless, Yeats lured Russell back into the fold as the Society transformed into a professional company under the patronage of Annie Horniman. In one of his most duplicitous and politically cunning moves, Yeats managed to convince Russell to advocate for the consolidation of power under the directors (Yeats, Gregory, and JM Synge) in order to make the outfit more professional and streamlined. Russell agreed and, as Yeats well knew, was able to use his well-earned goodwill with the actors to persuade them to ends Yeats never could. Russell, however, understood this was the end. When a section of the Society resigned in protest and formed their own group Cluithcheoirí na hÉireann, the Irish Players, Russell gave them permission to perform Deirdre announcing his split with Yeats and the Abbey Theatre.

While bitterness lasted, so did respect. Both men continued to recognize the genius of their respective poetry. Before the great split, Russell wrote to the American John Quinn that “I am always fighting with [Yeats], but if I hadn’t him to fight with it would make a great gap in my life.” And even when that gap existed, he defended Yeats poetry—especially his early poetry—as the greatest art to come out of Ireland. For Yeats’s part, he would come to recognize that his feelings about Russell and his art were projections. Thinking back on those contentious days, Yeats wrote “A.E. himself, then as always, I loved and hated, and when I read or saw [Deirdre], I distrusted my judgment, fearing it mere jealousy” (Auto 331-2).

What Macnie so wonderfully captures then is two men both drawn towards each other and repulsed by each other—“the antagonism that unites dear friends.” Their walk should lead them to friendship, but their various chin angles demonstrate their inability—and unwillingness—to look each other in the eye. They are, at this stage of their lives, old friends with old arguments and they simply cannot see eye to eye.

(3) MUSICAL REFLECTIONS:

Seamus Maguire (The Wishing Tree)

https://open.spotify.com/artist/77LnvDiKSK3gdN7gZmxzer?autoplay=true

Joep Beving (Ab Ovo)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6eDmID4jWs

Michael McHale (My Lagan Love)