Reflections across the Bog

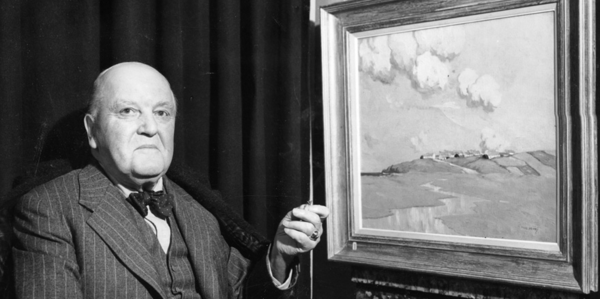

Paul Henry

Reflections across the Bog, circa 1919-1920

Paul Henry (Irish, 1877-1958), oil on canvas, The O'Brien Collection

The O'Brien Collection will lend Reflections across the Bog to the Snite Museum of Art in Spring 2022, to be a part of the exhibition Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022.

A Brief Biography of Paul Henry [Source: Bruce Stewart, Ricorso.net]

Paul Henry was born on 11 April 1877, University Rd., Belfast, one of four sons of Robert Michael Henry, Baptist minister (d. 1891), and his wife Kate Anne [née Berry]; ed. RBAI [var. Methodist college], apprentice designer Broadway Damask Co., Belfast; ed. Belfast School of Art, studying under Thomas Bond Walker from the age of 15, before moving to Paris, 1898. While there, he entered the famed Académie Julien and worked in Whistler’s studio; influenced by Impressionists Cézanne and Gauguin and by the peasant subjects of Millet; moved to London, 1900; shared rooms with Robert Lynd both there and in Guildford, Surrey, until 1912; loosely associated with Walter Sickert and the Fitzroy Street Group; married Grace (née Mitchell), also a painter; visited Achill on Lynd’s advice, 1910; struck by the rugged scenery and simple life of the people and influenced by J. M. Synge, whose works ‘touched some chord no other music ever had’; tore up his return ticket and remained on the island for ten years.

He settled in Dublin in 1919; painted The Lobster Fisherman at Dusk, 1920—his last to feature a human figure—preferring the idealized and contemplative natural scenes of in Dawn, Killary Harbour, 1922-23 [Ulster Museum], in colours reminiscent of Whistler’s cold tonality; his Connemara used as poster by London Midland & Scottish Railway Company, later providing the stereotypical view of the West of Ireland; elected RHA 1929; designed posters for London, Midland and Scottish Railway and Irish Tourist Board; lost much of his sight in 1945; lived in Bray thereafter; issued An Irish Portrait (1951), an unreliable autobiography; upon the passing of Grace in 1953, Henry remarried Mabel Young, herself also an accomplished artist.

Irish Times art critic Aidan Dunne wrote the following about Paul Henry:

‘[He] turned his back on a promising career in the London art world [... His] instinct was unerringly correct. Achill, which more or less became [Grace and his] home until 1919, when they moved to Dublin, was the making of Henry as an artist. It provided a rich fund of direct inspiration and served as a base for travels in the West and North West, allowing him to produce an exceptional body of work that occupies a central, pivotal place in the history of Irish art and still largely defines how we see the west of Ireland. / While his conversion to Achill was instantaneous and its impact on his work was immediately evident, he needed several years to devise a satisfactory way of dealing with the overwhelming qualities of environment of the western seaboard. His initial absorption in the texture of island life and the circumstances of the islanders themselves modulated only over a considerable time into a feeling for the landscape. And, while several of his paintings involve figures, on the whole his landscape work, exceptional in its spare intensity, represents the core of his artistic achievement.’ Further, [of contemporary Irish artists following the French manner:] ‘Problems arose when it came to the question of devising something distinctly their own based on the given, continental model.

… Some, like the exceptionally capable Roderic O’Conor, simply went absent without leave in terms of their Irishness. Henry had no strong political opinions or nationalistic leanings … His remarkable achievement was to take a contemporary artistic language and personalize it in relation to a specifically Irish subject matter, in a way that is both unmistakably Irish and stylistically challenging. If aspects of his work seem hackneyed to us now, it is because he became a victim of his own success, spawning countless imitations – including, admittedly, some self-imitation. [He was] enthusiastically adopted and promulgated by a Free State with a cultural profile to define and promote.’

‘Henry believed that the essence of Irishness, the country’s soul, is wrapped up in this face of the country and its people.’

Writing specifically about this piece, Henry biographer Dr. Brian Kennedy commented:

“The setting of this scene is probably the west of Ireland and in spirit it is close to several paintings Paul Henry made during 1918-19. Having decided to depart Achill Island in the latter year, he and his first wife, Grace, spent time looking for somewhere to live, before settling in Dublin, although briefly they had thought of moving north, as Paul had been born in Belfast. Yet, perhaps unexpectedly, their northern thoughts bore fruit for both of them and in the spring of 1919 they held a joint exhibition at Magee’s Gallery in Belfast. Reviewing that show, the News-Letter (17 April 1919) thought Paul had imparted to his landscapes ‘a depth of feeling ... [a] silence and mystery [which] belongs to the eternal order of things,’ a comment that well describes this bogland scene, “Reflections across the Bog.”

Many of Paul’s compositions from the time are similar in concept and execution to this piece. Great importance is given to the sky, with its heavy massing of clouds which define the mood of the scene. The landscape itself is reduced to a narrow band of terrain at the bottom of the picture plane and there is, for Henry, relatively heavy impasto to the paint surface, which is set down with great assurance and deliberation. The blue strip of distant hills, which separate the landscape from the sky, also halts the eye’s recession and the upward thrust of the dark turf stacks, which link these two areas, lends a feeling of theatricality to the composition and is a device commonly used by Henry throughout his career. This composition is a good example of Henry’s style and manner of execution at the time he left Achill—which was the defining point of his life —and before the often repetitive landscapes which, brought about by domestic and personal problems, predominate in his work of the 1920s.”

Dr. Brian Kennedy

Some thoughts from our Guest Curator this month,

Arabella Bishop, Senior Director, Sothebys, Ireland

Paul Henry’s: “Reflections across the bog”

Can anyone more readily transport you to the west of Ireland – a landscape of peat stacks, mountains, boglands, reflections, thatched cottages and ever changing light and weather - than Paul Henry?

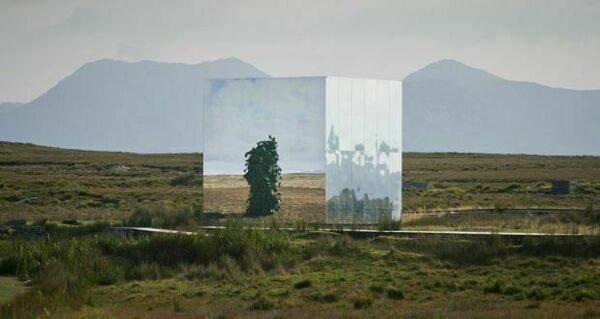

In this example, Henry devotes over half of the picture to the elements, beautifully conjuring cumulus clouds and driving rain, with pink hues filtering through. The downward brush work of the rain drawing our attention downwards to the bog below. Henry was a master of capturing the distinctive atmosphere of the West and his endless delight in rendering clouds puts him on a par with Constable and his famous cloud studies. Indeed, Henry’s constant visualization of the West ensures that, as S. B Kennedy wrote, ‘like Constable’s Suffolk and Cézanne’s Provence, once experienced it is difficult to see the landscape of the west other than through Henry’s eyes.’ Since Henry’s iconic rendering of the landscape, many artists have followed in his footsteps, enthralled to its magic. Perhaps one of the most engaging responses recently— and particularly to the theme of reflections which occupied Henry in the present work—has been John Gerrard’s recent installation, Mirror Pavilion which sat in Derrigimlagh Bog in Connemara as part of Galway International Arts festival.The West of Ireland will always elicit profound responses, and we can be grateful to the artists, poets and musicians who have conjured its spirit.

Derrigimlagh Bog in Connemara, where the second part of John Gerrard’s stunning large-scale installation, Mirror Pavilion, Leaf Work stands. Photograph: Ros Kavanagh

Music, perhaps "The West of Ireland" by the Boys of the Lough

Poetry: And Seamus Heaney's poem "Boglands" sums it up beautifully:

And from Marty Fahey …

Another musical piece that captures the sense of “The West” and its importance in the Irish psyche as a touchpoint of authenticity and identity

Link to the LUMIERE's The West's Awake